Levo – akcijska ponudba

Na srebrniku je snežni kristal z modro sredico, na hrbtni strani pa snežna princesa s krono in plaščem, okrašenim s snežnimi kristali.

Cena: 75,00 €

Na srebrniku je snežni kristal z modro sredico, na hrbtni strani pa snežna princesa s krono in plaščem, okrašenim s snežnimi kristali.

Cena: 75,00 €

Američani v finančnih poročilih vse večkrat omenjajo, da je zdaj eno glavnih vprašanj obstoj evropske monetarne unije in evra kot valute. Poudarjajo problem avstrijskih, italijanskih, švedskih bank, ki imajo predstavništva v vzhodnoevropskih državah in so z odobritvijo posojil že zdaj utrpele veliko izgubo, saj jim upniki ne zmorejo vračati posojenega denarja. Konec marca zapadejo plačila kvartalnih bančnih posojil, zato bo ta čas odločilni, sicer se bo sicer kriza še poglobila. Vsekakor obstaja veliko razlogov za večletno krizo kljub dejstvu, da so praktično vsi finančni strokovnjaki v svetu vključeni v njeno reševanje. Prav zato ostaja zlato dobra naložba.

Članek objavljamo v originalu.

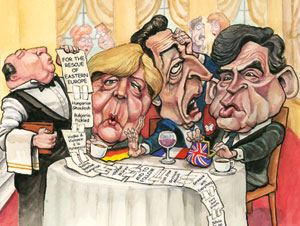

Eastern Europe’s woes

The bill that could break up Europe

If eastern Europe goes down, it may take the European Union with it

TUMBLING exchange rates, gaping current-account deficits, fearsome foreign-currency borrowings and nasty recessions: these sound like the ingredients of a distant third-world-debt crisis from the 1980s and 1990s. Yet in Europe the mess has been cooked up closer to home, in east European countries, many of them now members of the European Union. One consequence is that older EU countries will find themselves footing the bill for clearing it up.

Many west Europeans, faced with severe recession at home, will see this as outrageously unfair. The east Europeans have been on a binge fuelled by foreign investment, the desire for western living standards and the hope that most would soon be able to adopt Europe’s single currency, the euro. Critics argue, with some justice, that some east European countries were ill-prepared for EU membership; that they have botched or sidestepped reforms; and that they have wasted their borrowed billions on construction and consumption booms. Surely they should pay the price for their own folly?

Yet if a country such as Hungary or one of the Baltic three went under, west Europeans would be among the first to suffer (see article). Banks from Austria, Italy and Sweden, which have invested and lent heavily in eastern Europe, would see catastrophic losses if the value of their assets shrivelled. The strain of default, combined with atavistic protectionist instincts coming to the fore all over Europe, could easily unravel the EU’s proudest achievement, its single market.

Indeed, collapse in the east would quickly raise questions about the future of the EU itself. It would destabilise the euro—for some euro members, such as Ireland and Greece, are not in much better shape than eastern Europe. And it would spell doom for any chance of further enlarging the EU, raising new doubts about the future prospects of the western Balkans, Turkey and several countries from the former Soviet Union.

The political consequences of letting eastern Europe go could be graver still. One of Europe’s greatest feats in the past 20 years was peacefully to reunify the continent after the end of the Soviet empire. Russia is itself in serious economic trouble, but its leaders remain keen to exploit any chance to reassert their influence in the region. Moreover, if the people of eastern Europe felt they had been cut adrift by western Europe, they could fall for populists or nationalists of a kind who have come to power far too often in Europe’s history.

How to avert disaster

The question for western Europe’s leaders is how best to avert such a disaster. Although markets often treat eastern Europe as one economic unit, every country in the region is different. Three broad groups stand out. The first includes countries that are a long way from joining the EU, such as Ukraine. Here European institutions may help financially or with advice, but the main burden should fall on the International Monetary Fund. These countries will have to take the IMF medicine of debt restructuring and fiscal tightening that was meted out so often in previous emerging-market crises.

Things are different for the countries farther west, all EU members for which the union must take prime responsibility. One much-touted remedy is to accelerate their path to the euro, or even let them adopt it immediately. It might make sense for the four countries with exchange rates pegged to the euro: the Baltic trio of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, plus Bulgaria. (Slovenia and Slovakia have joined the euro already.) None of these will meet the Maastricht treaty’s criteria for euro entry any time soon. But they are tiny (the Baltics have a population of barely 7m), so letting them adopt the euro ought not to set an unwelcome precedent for others nor should it damage confidence in the single currency. Yet the European Central Bank and the European Commission firmly oppose this form of “euroisation”, even though two Balkan countries, Montenegro and Kosovo, use the euro already.

Unilateral or accelerated adoption of the euro would make far less sense for a third group of bigger countries with floating exchange rates: the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania. None of these is ready for the tough discipline of a single currency that rules out any future devaluation. Their premature entry could fatally weaken the euro. But as their currencies slide, the big vulnerability for the Poles, Hungarians and Romanians, especially, arises from the debt taken on by firms and households in foreign currency, mainly from foreign-owned banks. What once seemed a canny convergence play now looks like a barmy risk, for both the borrowers and the banks, chiefly Italian and Austrian, that lent to them.

Stopping the rot

The first priority for these four must be to stop further currency collapse. The second is to prop up the banks responsible for the foreign-currency loans that are going bad. The pain of this should be shared four ways: between the banks and their debtors, and between governments of both lending and borrowing countries. From outside, these two tasks will necessitate help from several sources: the European Central Bank as well as the IMF, the commission’s structural funds, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and perhaps the European Investment Bank. Given the scale of the problem, the lack of co-ordination between these outfits has been scandalous. A third aim must be to get eastern European countries to restart the structural reforms they have evaded thus far.

Bailing out the same mythical Polish plumbers who just stole everybody’s jobs will be hard for Europe’s leaders to sell on the doorsteps of Berlin, Bradford and Bordeaux, especially with the xenophobic right in full cry. German taxpayers are already worried that others are after their hard-earned cash (see article). The bill will indeed be huge, but in truth western Europe cannot afford not to pay it. The meltdown of any EU country in the region, let alone the break-up of the euro or the single market, would be catastrophic for all of Europe; and on this issue there is little prospect of much help from America, China or elsewhere. It is certainly not too late to rescue the east; but politicians need to start making the case for it now.

Vir: The Economist

© Moro & Kunst 2025

Naša spletna stran uporablja piškotke za izboljšanje uporabniške izkušnje. Informacije - piškotki, so shranjeni v vašem brskalniku. Ob obisku naše spletne strani s pomočjo piškotkov npr. ugotovimo kaj vas zanima, kakšen jezik ste izbrali ali pa kaj vse imate v nakupovalni košarici. Piškotki v nobenem primeru ne morejo poškodovati vašega računalnika ali pa nam omogočiti osebno prepoznavo obiskovalcev.

Nujno potrebni piškotki bi naj bili omogočeni ves čas. Brez njih ne moremo zagotavljati pravilnega prikaza in delovanja naše spletne strani.

Če teh piškotkov ne omogočite, boste ob vsakem obisku naše spletne strani soočeni s ponovno izbiro nastavitev piškotkov.

To so običajno piškotki, ki skrbijo za anonimno spremljanja obiskov na naši spletni strani. Na ta način ugotavljamo katere vsebine še posebej zanimajo naše obiskovalce in podobno.

Prosimo omogočite nujno potrebne piškotke, da si bomo lahko zapomnili vašo izbiro nastavitev.

Več podatkov o zasebnosti na naši spletni strani.